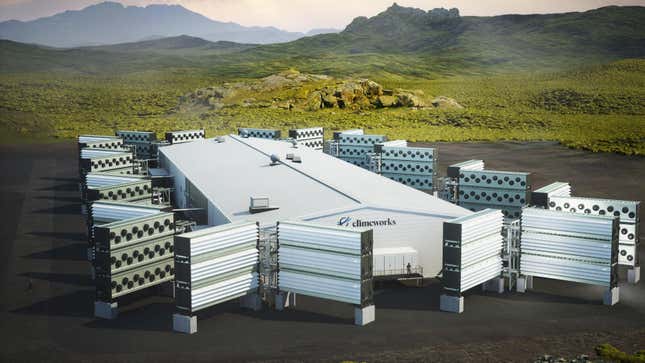

A Swiss company just set up a giant ‘vacuum cleaner’ that will suck as much as 36,000 metic tons of carbon out of the atmosphere every year.

CNN reports that Climeworks’s Mammoth project, which is two years into building, will be 10 times more effective than its previous efforts. Mammoth will be able to operate up to 72 air scrubbers, though it only has 12 going at the moment.

Climeworks, which markets itself as a compliment to corporate sustainability efforts and raised $650 million a couple years ago to do so, hopes to scale up to removing a million metric tons of carbon from the atmosphere a year by 2030, CNN reports. The company’s clients include Microsoft, whose 2022 climate disclosure says it was responsible for nearly 13 million metric tons of carbon emissions, and H&M Group, whose 2023 climate disclosure says it was responsible for more than 8 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions.

The Earth is running out of time to halt a global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius beyond pre-industrial levels. After that, the planet will become increasingly inhospitable to human life, far beyond the devastating effects of climate change that we’re already seeing such as the droughts driving up cocoa prices and sea-level rises threatening coastal cities everywhere. Much of that warming is due to carbon emissions that trap the sun’s heat in the atmosphere. The Climeworks device is designed to fight that.

Direct air capture, DAC, takes CO2 from the air then stores it deep underground, or converts it into products.

Some people are critical of the technology. Jonathan Foley, executive director of the climate non-profit Project Drawdown, wrote in Scientific American in December that such projects remove too little carbon and themselves consume too much (possibly carbon-emitting) energy to live up to the hype that surrounds them. Instead, he writes, efforts should be focused on directly reducing emissions in the first place.